Grid-forming proposals + VGF tenders are quietly raising the bar for who can scale storage in India.

There’s a simple way to decode India’s BESS market right now: we’re moving from buying MWh to buying grid behaviour.

Two things happened in the last week that point to the same structural shift.

First, Grid-India floated a discussion paper proposing that all new BESS installations of 50 MW and above should incorporate grid-forming capability (especially in weak grids/remote areas). Second, tenders in Gujarat and Andhra are steadily scaling “standalone BESS” under VGF-backed, schedule-driven contracts.

Put together, these are not random announcements. They’re the beginnings of India’s “storage quality layer” where batteries won’t be treated as passive energy reservoirs but as active grid assets that must stabilise, respond, and survive bad grid conditions.

What changed structurally (signal vs noise)

Signal: The market is moving toward storage that can deliver stability services (voltage/frequency support, fault response, low-SCR operability), not just energy shifting.

Noise: Another tender headline about MW/MWh without asking: “What will this BESS do when the grid gets ugly?”

What happened (facts, not flavour)

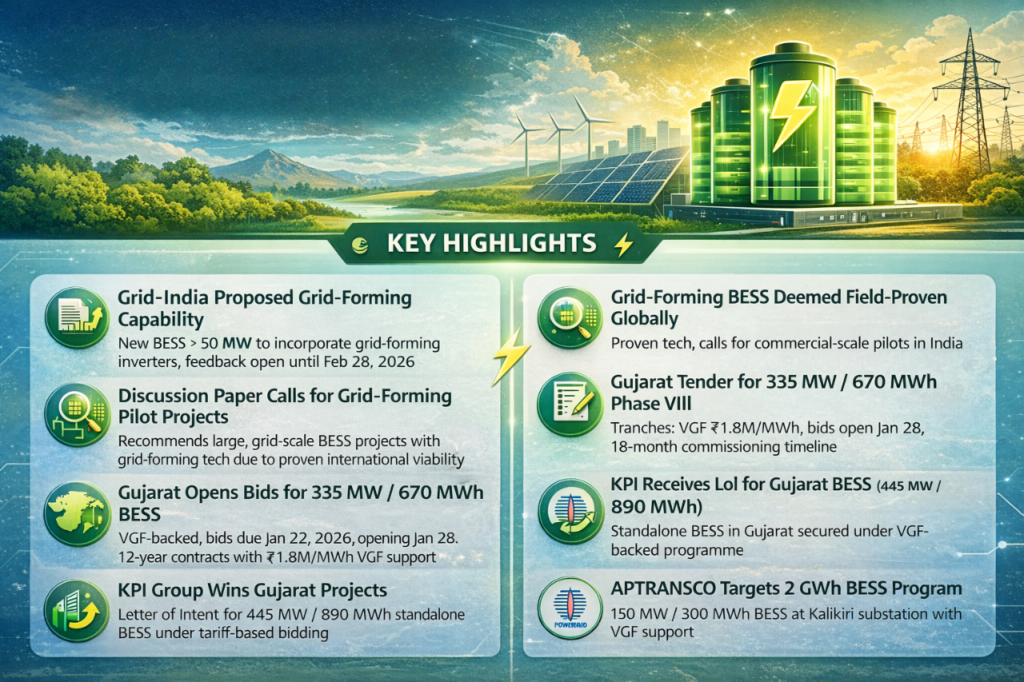

- Grid-India proposed that new BESS installations of 50 MW+ incorporate grid-forming capability, with stakeholder feedback open until February 28, 2026.

- The discussion paper argues grid-forming inverter tech is becoming commercially viable and field-proven internationally, and recommends large, grid-scale pilot projects around BESS-backed grid-forming inverters.

- Gujarat’s state utility holding company invited bids for 335 MW / 670 MWh standalone BESS (Phase VIII), with bids due January 22, 2026, and opening on January 28.

- The Gujarat tender includes VGF of ₹1.8 million per MWh, disbursed in tranches (20% at financial closure, 50% at COD, 30% one year after COD).

- The Gujarat contract tenor is 12 years from full commissioning, with a scheduled commissioning timeline of 18 months from the agreement effective date.

- KPI Group’s arm received an LoI for 445 MW / 890 MWh standalone BESS projects in Gujarat under a tariff-based competitive bidding process linked to the VGF-backed programme.

- POWERGRID received a letter of award to set up a 150 MW / 300 MWh (2-hour) standalone BESS at the 400/220 kV Kalikiri substation (Chittoor district, Andhra Pradesh) under BOO with VGF support, as part of an APTRANSCO programme targeting 2,000 MWh across substations.

Why this matters (and to whom)

1) Market/strategy implication

VGF-backed tenders are doing something important: they are turning storage into an infrastructure category with predictable contracting logic. But now grid-forming proposals are adding a second filter: it’s not enough to bid aggressively, you have to execute grid-grade performance. That reduces the “spray-and-pray EPC” path. It favours players with deep inverter controls, strong commissioning discipline, and credible O&M.

2) Technical/infra implication

Grid-forming is not a checkbox. It’s a design posture. Controls, protection coordination, fault response, reactive power behaviour, and stability in low short-circuit ratio environments become front and centre. That hits everything:

- inverter choice and control architecture,

- test & validation scope,

- integration time at substation,

- commissioning risk,

- and long-run uptime metrics.

India’s grid is absorbing more inverter-based resources (RE, data centres, new loads), while synchronous generation’s stabilising “muscle” isn’t always where you need it. The Grid-India paper basically says: if you’re going to add big BESS, make sure it behaves like a grid partner, not a grid guest.

3) Policy/regulatory/capital implication

Once grid-forming expectations start appearing in tender specs (explicitly or implicitly), financiers will treat controls maturity and commissioning capability as underwriting criteria. The “lowest tariff wins” era quietly shifts toward “lowest tariff that can actually reach COD and meet performance.” Expect tighter technical due diligence, stronger performance guarantees, and more serious penalty clauses around non-availability.

Execution Risk Ledger (what can break on-ground)

- Controls–protection mismatch at substations: grid-forming behaviour can clash with existing protection settings if not engineered carefully.

- Commissioning delays due to test scope creep: grid-forming pilots and validation can expand timelines beyond standard 2-hour BESS commissioning playbooks.

- Heat + harmonic stress on power electronics: poor thermal design and harmonic management will show up as derating and downtime.

- Weak-grid surprises: remote/weak nodes behave differently under faults; simulation assumptions often meet reality with a slap.

- O&M capability gap: long-term availability depends on spares, trained field teams, and telemetry discipline, not just warranty paperwork.

Who wins / who gets squeezed

Who wins

- EPC/OEMs with strong inverter controls + grid integration references.

- Developers who can reliably hit COD and maintain availability with disciplined O&M.

Who gets squeezed

- Players bidding on price without controls/commissioning depth.

- Storage integrators relying on loosely coordinated multi-vendor stacks (more interfaces = more failure modes).

Operator actions (next 90 days)

- [DISCOM/SLDC] Start defining what “grid support” means operationally: events, response times, telemetry, and how you’ll verify it.

- [CPO/IPP] Build a grid-forming readiness checklist: controls, protection studies, test plan, telemetry, cyber access model.

- [Investor] Add “commissioning complexity” and “grid integration competence” to diligence, not just battery supply contracts.

- [Policymaker] Clarify how grid-forming performance will be measured and enforced, so specs don’t become vague compliance theatre.

- [OEM] Prepare for traceable performance data requirements (event logs, thermal events, cycle history), because this is where standards tend to go.

- [EPC] Lock spares + service capability early; availability will become the hidden KPI behind every “lowest tariff” headline.

Questions for the Ecosystem

- If BESS above 50 MW needs grid-forming, should tenders start paying explicitly for stability services, not just capacity?

- Who carries the risk when grid-forming controls interact badly with legacy protection schemes: OEM, EPC, or the grid operator?

- Does India need a standardised “grid-forming test protocol” before scale-up becomes messy?