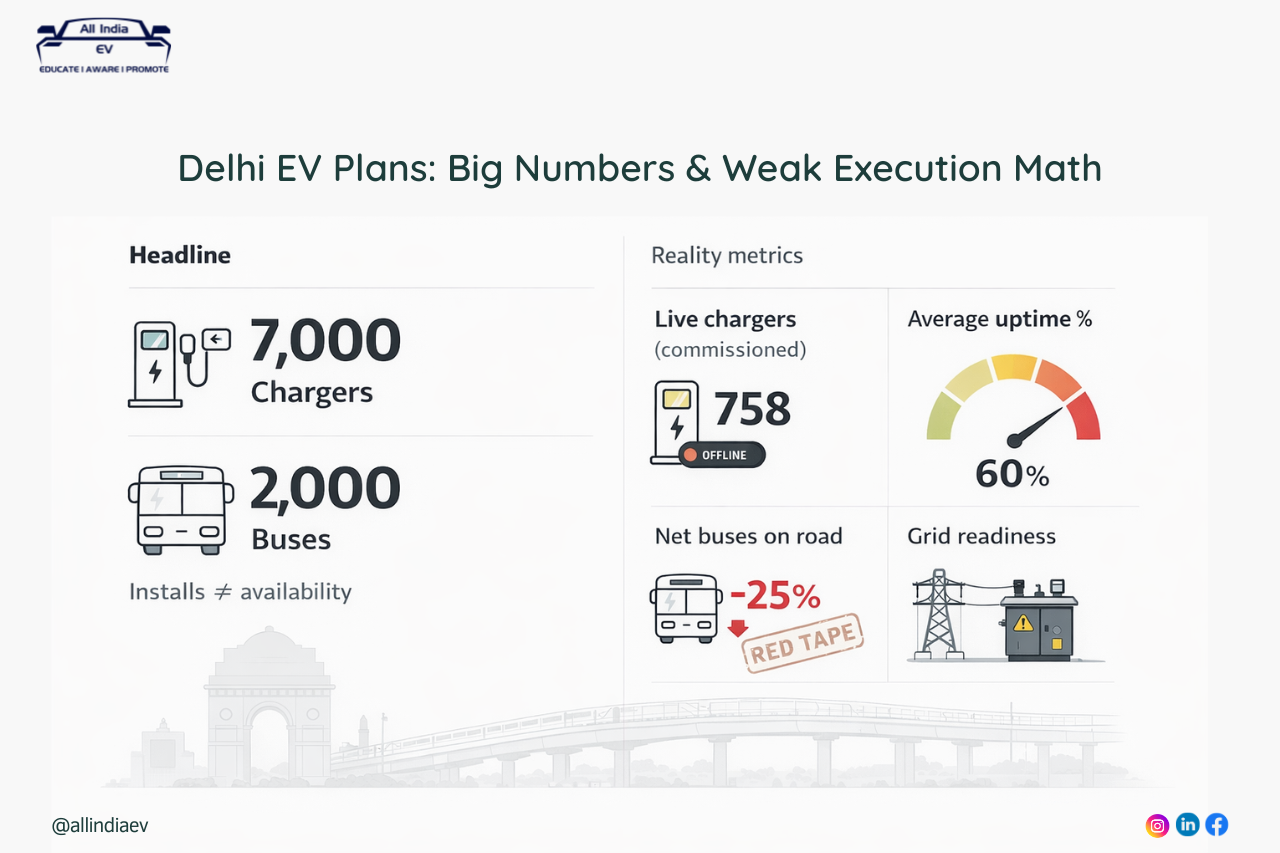

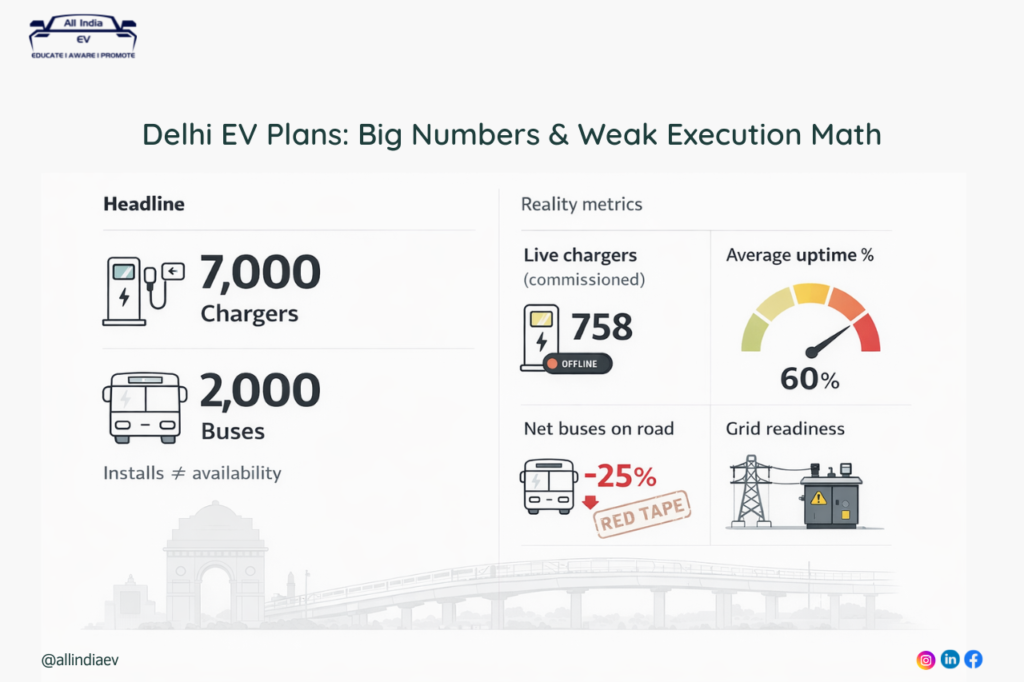

Delhi wants to add ~7,000 EV charging stations by end-2026 and bring in ~2,000 buses (with an internal target of 2,468 buses this year in a month-wise plan), as part of its air-pollution response.

Here’s the blunt truth: this is achievable only if Delhi runs it like an infrastructure delivery program with hard milestones and uptime accountability.

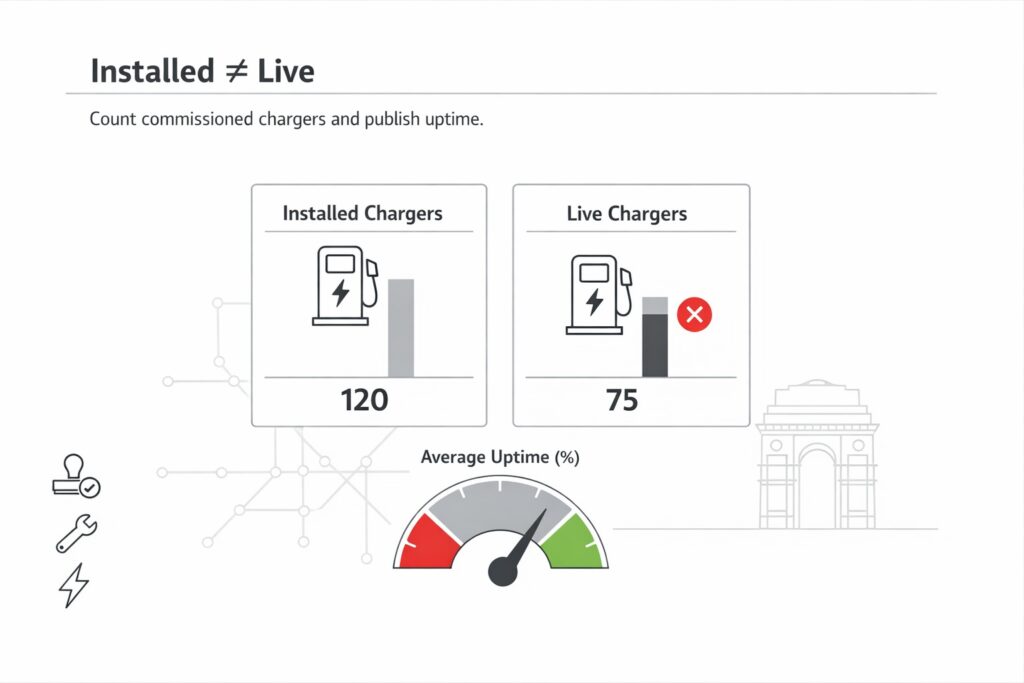

If Delhi runs it like a “counting installs” campaign, the city will get paper progress, not cleaner air.

1) The charger headline is misleading even before execution starts

Delhi’s own numbers (as reported) say it had 8,849 charging stations as of December against a projected requirement of 36,150, leaving a deficit of 27,301.

Add 7,000 and the total becomes 15,849. That still leaves Delhi less than halfway to the projected requirement.

So no, “7,000 chargers” does not solve Delhi’s charging gap. At best, it reduces the deficit. If the plan is being sold as a decisive fix, it’s not.

2) “7,000 in a year” is not hard because of hardware. It’s hard because of sites and operations

7,000 stations means a sustained run-rate. That’s not a tech problem. That’s a permissions + civil works + power connection + commissioning + O&M problem.

It has been said these chargers will be installed at Rapid Rail and Delhi Metro stations, and installed by power distribution companies (DISCOMs). That sounds neat, but it hides the real constraints:

- Most locations are not “plug-and-play.” Parking design, cable routing, safety clearances, and public movement matter.

- O&M is where India’s public charging often dies. A charger installed is not a charger available. Downtime turns “charger count” into fiction.

- Uptime metrics are not being published. If you can’t tell people what % of chargers are live on a given day, the number is marketing.

If Delhi wants credibility, it should publish two numbers monthly:

- Chargers commissioned (live)

- Average uptime (%)

Without uptime, your air-pollution plan becomes a photo-op plan.

3) Chargers are a grid project pretending to be a transport project

Charging doesn’t scale on announcements. It scales on:

- transformer upgrades,

- feeder strengthening,

- sanctioned load approvals,

- and fault response time.

If DISCOMs are leading installs, good. But then Delhi needs a public, transparent grid-readiness plan. Otherwise, what happens is predictable:

- chargers cluster where grid is already strong,

- weak-grid neighborhoods remain underserved,

- utilisation becomes uneven, and chargers look “unused,” which then becomes an excuse to slow investment.

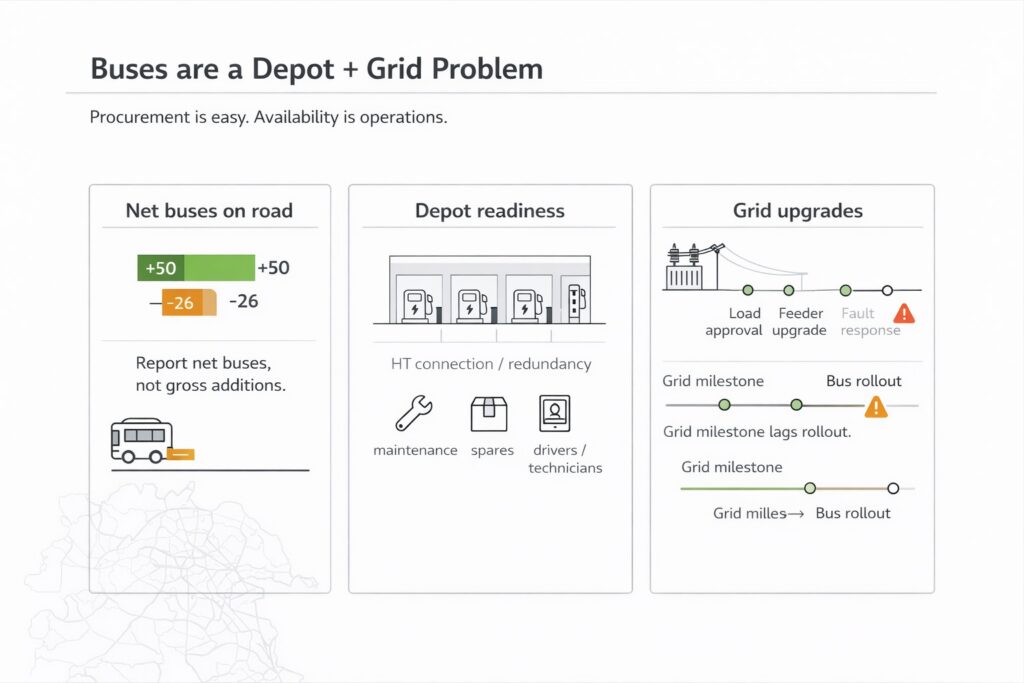

4) The bus plan is the bigger risk, because buses come with depots, not just purchase orders

Delhi’s own review meeting reportedly said the city needs 11,000 buses. Today it operates 5,245 buses, including 3,377 electric buses.

The month-wise plan target reported is 2,468 new buses this year, but the reporting also admits a problem: older CNG buses may be phased out, and the government still has to “factor in” the net impact.

Translation: even if Delhi “adds” buses, the public experience may not change much if retirements offset additions.

Now the real execution bottlenecks for adding e-buses at scale:

- Depot power readiness: bays, chargers, HT connections, redundancy

- Route planning: bus availability depends on scheduling, not just fleet size

- Drivers and technicians: e-bus scale fails when staffing lags

- Spares and repair cycles: a few missing components can park dozens of buses

The announcement is about procurement. The real work is about depots and uptime.

5) Delhi’s EV policy expiry is an immediate governance deadline

The existing EV policy reportedly expires end of March 2026, and a revised policy is expected by then.

That’s not a footnote. It’s a gating item. If the new policy introduces friction, delays, or unclear roles across agencies, the 2026 rollout will slow down even if funding exists.

So is it possible? Yes. But only if Delhi changes how it measures success.

What Delhi must do (non-negotiables)

- Stop counting “installed chargers.” Count “live chargers” and publish uptime monthly.

- Standardise site templates (metro/rail stations, markets, government complexes, depots) so 7,000 doesn’t become 7,000 custom projects.

- Lock O&M contracts upfront with clear penalties for downtime and slow repair cycles.

- Publish a grid-upgrade map (even a simple feeder/transformer milestone plan) so rollout doesn’t become geographically biased.

- For buses, publish “net buses on road” after retirements, not gross additions.

- Treat depots as energy infrastructure: power upgrades first, buses second.

- Put staffing targets in public: drivers trained, technicians hired, spares positioned.

If Delhi does these, the plan can move from announcement to execution.

If Delhi does not do these, here’s what will happen:

- chargers will exist, but many will be dead,

- buses will be procured, but availability will disappoint,

- and air pollution will remain a seasonal crisis with a yearly “new target” cycle.

Bottom line

Delhi can do it. But right now, the plan reads like a headline designed for urgency, not a program designed for delivery.

Air quality won’t improve because the city “added” chargers and buses on paper.

It improves when chargers stay live and buses stay on road.